Anna May Navarrete

Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Erasmus Mundus joint

degree “International Master of Early Childhood Education and Care”

Oslo and Akershus University College of Applied Sciences

Dublin Institute of Technology

University of Gothenburg

University of Malta

August 2015

DECLARATION

I hereby certify that the material which is submitted in this thesis towards the award of the

Masters in Early Childhood Education and Care is entirely my own work and has not been

submitted for any academic assessment other than part-fulfilment of the award named

above.

Signature of candidate:

August 2015

ABSTRACT

Anna May Navarrete

Assessment in the Early Years: The Perspectives and Practices of Early Childhood

Educators

In recent years there has been growing attention on the importance of assessment in early childhood education, especially in relation to supporting children’s learning. The present study aimed to investigate early childhood educators’ perspectives and practices regarding assessment in the early years. In particular, the meanings and values which educators ascribe to assessment were explored. Moreover, the study focused on strategies educators employed, along with the associated support and challenges relating to their assessment practice. Adopting a qualitative design, in-depth interviews were conducted with eight educators from different settings, and thematic analysis was used to identify emergent themes. Subsequently, information from assessment tools that educators used in practice were collected and analysed. Findings show that educators hold diverse views and have varying approaches to assessment, using different tools and methods. Nevertheless, participants agree that assessment is important for supporting children’s learning and development. Data suggests that collaboration plays some role in aiding assessment practice, particularly collaborating with colleagues and parents; however, findings also indicate that children have limited participation in the assessment process. The study also suggests that time, structural factors, qualification and training contribute to the ease in which assessment is carried out. Delving into educators’ perspectives and practices on early years’ assessment can offer insight on what actually happens in settings and the thoughts and attitudes that direct them, while shedding light on different issues they are faced with. The author hopes that the findings of the study can direct future research investigating issues surrounding assessment practice, greater collaboration with families, and children’s agency in assessment.

International Masters in Early Childhood Education and Care

August 2015

Keywords: early years’ assessment, educators’ perspectives, assessment practices

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This dissertation is the culmination of the wonderful journey I have had with the IMEC programme, which I would not have had the opportunity to experience without the work and dedication of the professors and institutions spearheading it – Oslo and Akershus University College of Applied Sciences, University of Gothenburg, Dublin Institute of Technology and University of Malta.

I would like to express my utmost gratitude towards my supervisor, Dr. Ann Marie Halpenny for her invaluable insight and guidance, and Dr. Máire Mhic Mhathúna and Cathy Kelleher for their assistance during this term. I would also like to thank Nuraisha Atar for the constant support throughout the research process, and Eya Oropilla for the help and encouragement. To my IMEC classmates, these past two years have been a blur of exciting adventures. Thank you for enriching my life and allowing me to expand my horizons in ways I didn’t know were possible. I would also like to acknowledge the settings that welcomed me, and the educators whose narratives were vital to this endeavour.

Many thanks also to my Every Nation Dublin family and to the Gramonte family for their generosity and hospitality. And to my mama, papa, and John Mark, a million thanks for your love and unending support and trust in me.

All glory and honour to God, who has sustained and strengthened me throughout it all.

LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES

List of Tables

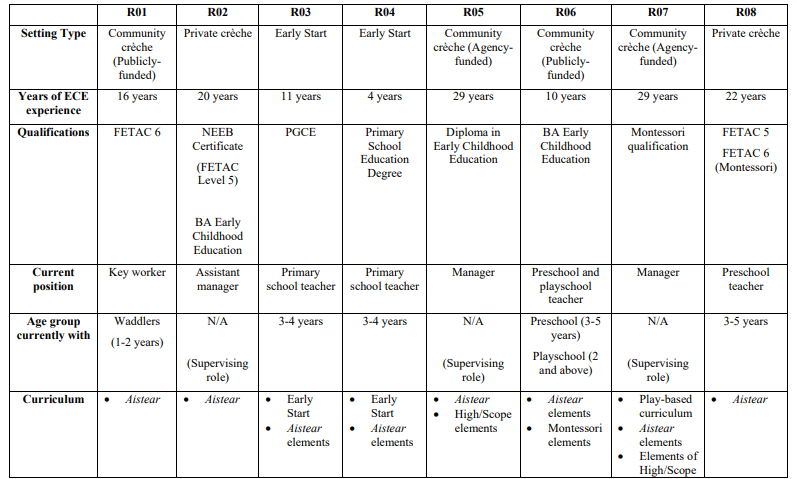

Table 1. Participant Composition

List of Figures

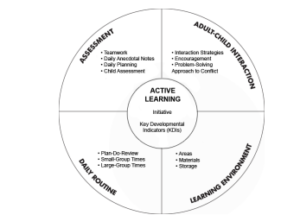

Figure 1. The High/Scope Preschool “Wheel of Learning” (Hohmann et al., 2008, p. 6)

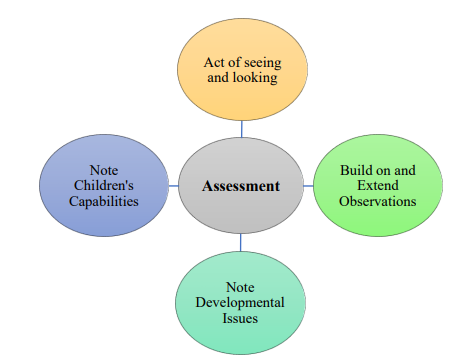

Figure 2. Educators’ Understanding of Assessment

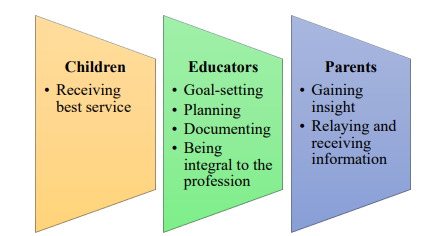

Figure 3. Value of Assessment According to Participants

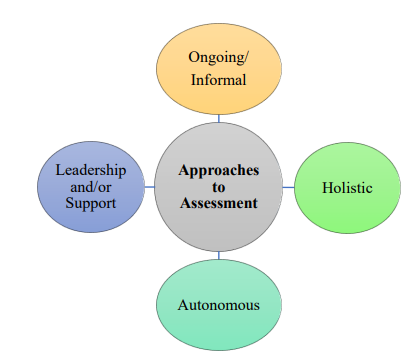

Figure 4. Educators’ Approaches to Assessment

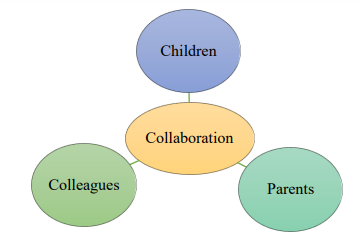

Figure 5. Collaboration in Assessment

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DECLARATION

ABSTRACT

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1 Introduction

1.2 Context of the research

1.3 Rationale for the research

1.4 Research aims and objectives

1.5 Methodology

1.6 Scope and Limitations

1.7 Glossary of Terms

1.8 Research Overview

CHAPTER 2: LITERATURE REVIEW 2.1 Introduction

2.2 Perspectives on Children and Children’s Learning

2.2.1 Developmental Perspective

2.2.2 Socio-cultural Perspective

2.2.3 Child’s Rights Perspective

2.3 Curriculum, Pedagogy, and Assessment

2.4 Models of Early Childhood Education

2.4.1 Montessori Approach

2.4.2 High/Scope Curriculum

2.4.3 Reggio Emilia

2.5 Focusing in on assessment in the Early Years

2.5.1 A broad look at assessment

2.5.2 Aistear, the Irish Early Years Framework

2.5.3 Partnership in Assessment

2.5.4 Zooming in on documentation

2.5.5 Factors affecting assessment practice

CHAPTER 3: DESIGN AND METHODOLOGY 3.1 Introduction

3.2 Research Aim and Questions

3.3 Methodological Approach

3.3.1 Reflexivity

3.4 Participants

3.4.1 Research Sites

3.4.2 Participant Composition

3.5 Data Generation

3.5.1 Research Instruments

3.5.2 Research Procedure

3.6 Data Analysis

3.7 Ethical Considerations

3.8 Limitations

CHAPTER 4: FINDINGS 4.1 Introduction

4.2 Educators’ Understanding of Assessment

4.3 Values Educators Ascribe to Assessment

4.4 Educators’ Approaches to Assessment

4.5 Educators’ Methods for Assessment

4.5.1 Strategies for Assessment

4.5.2 Tools for Assessment

4.6 Factors Affecting Assessment

4.6.1 Challenges to Assessment

4.6.2 Support in Assessment

4.7 Recommendations for Enhancing Practice

4.8 Summary

CHAPTER 5: DISCUSSION OF FINDINGS 5.1 Introduction

5.2 Assessment as Process and Product

5.3 A Diverse Delivery of Assessment Practice

5.3.1 Aistear as the Unifying Thread

5.4 Assessment as a Shared Practice

5.5 Factors Affecting Assessment Practice in the Early Years

5.6 Limitations

CHAPTER 6: CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 6.1 Conclusion

6.2 Recommendations

REFERENCES

APPENDICES

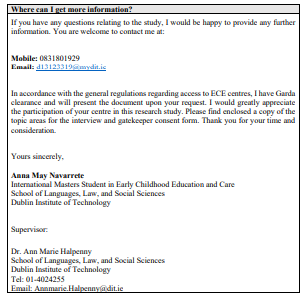

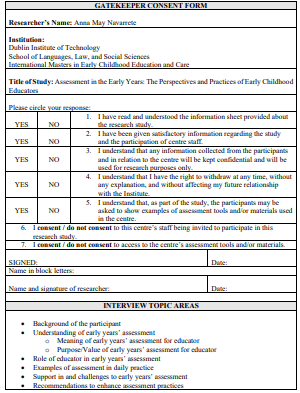

APPENDIX 1: INFORMATION KIT FOR GATEKEEPERS

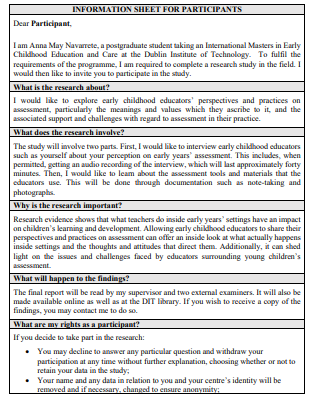

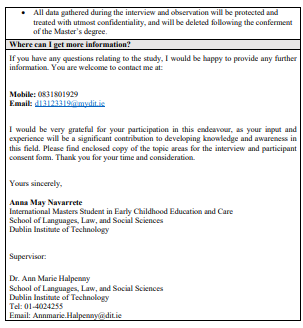

APPENDIX 2: INFORMATION KIT FOR PARTICIPANTS

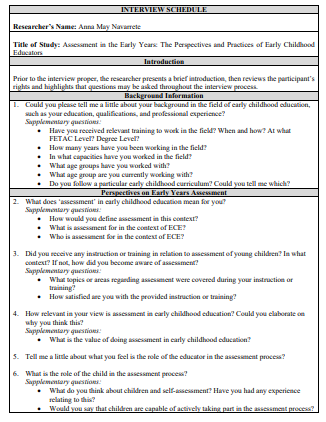

APPENDIX 3: INTERVIEW SCHEDULE

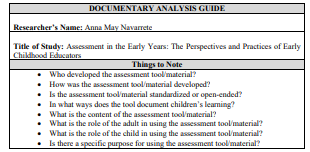

APPENDIX 4: DOCUMENTARY ANALYSIS GUIDE

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION

1.1 Introduction

Inherent in young children is the desire to learn and make sense of their immediate world, and the role that adults play is significant in guiding their development (Duffy, 2010; French, 2007). Adults are essential in providing an environment that supports children in the course of their learning (Hattie, 2009; Whitebread, 2008), and in early childhood education (ECE) settings, it is the educators who hold this responsibility.

Assessment, which is an integral part of the curriculum (Dunphy, 2008), can be regarded as a vehicle to facilitate the process of learning and development inside ECE settings. The perception of assessment in ECE has moved beyond that of screening and diagnosis, and now encompasses answering questions about the child or providing information about classrooms and programs (Snow & Van Hemel, 2008). As a result, the information obtained from assessments is not only a manifestation of the child’s skills and potentials, but also the adequacy of the settings they are embedded within.

1.2 Context of the research

Provision of ECE services in Ireland is diverse, ranging from centre-based services such as crèches or nurseries, sessional services, and after school programmes, to more informal childcare arrangements such as childminding (Corbett, 2012; Department of Education and Science [DES], 2004). Over the past decades, the momentum in the field of ECE in Ireland has moved forward positively, where shifting views about learning and development in the early years have created a deeper understanding and appreciation of the discipline (Corbett, 2012). Although it was suggested that more consideration be given to adapting the system to young children’s learning characteristics, the OECD Thematic Review of Early Childhood Education and Care Policy in Ireland indicated that the aspect of early childhood education within the primary school is well-established and respected (DES, 2004). The Primary School Curriculum, which is relevant for children from four until six years, considers assessment as important for effective and successful teaching and learning (DES, 1999). There has also been an effort to address issues related to access of services through the ECCE Scheme, granting a free year of preschool to children (Citizens Information Board, 2014). And more recently, Early Years Education-focused Inspections have been introduced to the sector, to emphasize and ensure quality of early education being provided by the ECCE scheme (DES, 2015). In addition, key documents have been created to act as guides for the content and quality of the services provided. Síolta: The National Quality Framework for Early Childhood, introduced in 2006, focuses on supporting services in achieving and maintaining quality in settings catering to children from birth to six years (Duignan, 2012). Aistear, on the other hand, is a curriculum framework for children from birth to six years published in 2009, discussing themes relating to child development and providing strategies to promote it (National Council for Curriculum and Assessment [NCCA], 2009). Assessment is a significant feature in this framework, being illustrated as a form of good practice. Together, Síolta and Aistear are complementary resources aiming to raise the quality of ECE services in Ireland.

1.3 Rationale for the research

The focus of the present study has arisen as a result of a number of factors. From a personal point of view, assessment in the early years emerged as a topic of interest for the researcher from her background in university teaching1 . Handling an undergraduate course in assessment of preschool children while leading a preschool class in a laboratory child centre has allowed the researcher to apply theory in practice and appreciate the value of assessment in the field of ECE. Furthermore, exploring the diverse perspectives on children’s learning and development has nurtured the researcher’s desire to further engage with the topic and examine critical issues within it.

A number of developments within the policy context contribute to the rationale for the present study. ECE policies that have been developed in recent years have been influenced, in part, by the recognition of the importance of child development, the acknowledgement of young children as citizens in their own right, and socio-economic changes within society (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 2006). In illustrating

1 The researcher was employed as a University Instructor, responsible for teaching undergraduate classes in the department while leading a preschool class in the laboratory child centre.

he contribution of education and care to a national framework for early learning, Hayes (2007) notes that stakeholders are increasingly interested in children’s learning characteristics and how others can support this, going beyond a prescriptive role.

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child stresses the necessity of a relevant curriculum to the child’s life and needs, and one which promotes the development of holistic skills (Hodgkin & Newell, 2007). In the second OECD review of how stakeholders support children’s learning and development, teaching and curriculum standards, the pedagogical relationship between children and educators, as well as child-outcome quality were included, among others, in aspects of quality examined in evaluating early childhood systems (OECD, 2006). Assessment plays a key role in constructing meaningful curriculum (National Research Council, 2001) that promotes quality service for children’s learning and development.

Researchers have also begun to look into underlying processes that influence the development of young children. The Effective Pre-school and Primary Education (EPPE) project was a large-scale study that investigated the effects of pre-school provision in the UK, and found that good child outcomes were associated with formative feedback to children and regular communication to parents regarding children’s progress (SirajBlatchford, 2010). Similarly, during the consultation phase of the development of Aistear, the importance of supporting children’s learning through observing and listening to them was highlighted, with recommendations of incorporating this finding into the framework (Daly & Forster, 2012). Communication with families, observation, and listening are important aspects of assessment that can support children in their experience in early years’ settings (NCCA, 2009).

These key documents and studies underscore the value of educators, and what they do, in ECE settings, and as more centres offer longer hours for their services, there is a need to reflect on children’s experiences in these settings and whether the provision they receive is appropriate to their needs (Duffy, 2010). Allowing early childhood educators to share their perspectives and practices on assessment can offer an inside look at what actually happens inside classrooms and the thoughts and attitudes that direct them. Additionally, it can shed light on the issues and challenges faced by educators surrounding young children’s assessment.

1.4 Research aims and objectives

In light of the growing attention to and awareness of the importance of assessment in early childhood education, this study aims to investigate early childhood educators’ perspectives regarding assessment in the early years, focusing on children from birth to five years. In particular, the study sets out to explore the meanings and values which early childhood educators ascribe to assessment, their strategies in doing assessment, and the associated support and challenges with regard to assessment in their practice.

The study aims to answer the following questions:

1. What meanings do early childhood educators ascribe to assessment?

2. What value does assessment hold for early childhood educators?

3. What approaches and strategies do early childhood educators use for assessment?

4. What support and challenges do early childhood educators experience in doing assessment within their settings?

1.5 Methodology

A qualitative approach was used in the study, informed by an Interpretivist paradigm. Through purposive sampling, eight early childhood educators working with children from birth to five years were gathered as participants for the research. In-depth interviews, as well as documentary analysis, were utilised as methods for data gathering. The in-depth interviews sought to explore educators’ understanding and perspectives on assessment, while giving space for them to provide self-reports of their own assessment practices. Documentary analysis served as a supplement to the data gathered through interviews, examining the different assessment tools and materials educators use in ECE settings.

All information regarding methodology and research design was submitted to the ethics board in the Dublin Institute of Technology for approval. Informed consent was sought from all stakeholders concerned in the study, and the identity of the participants, as well as the settings they work in, was kept confidential and anonymised throughout the data collection process, beginning with the transcription of data to the final write-up of the results and discussion.

1.6 Scope and Limitations

This study focuses on assessment in relation to children’s participation, learning, and typical development, and does not cover assessment as a means for developmental screening or diagnosis. The methodological limitations associated with the study will be further explained in Chapter Three.

1.7 Glossary of Terms

For the purpose of this study, the following terms will be used throughout to cover a number of concepts:

Early Childhood Education (ECE) – Represents the field that advocates for the wellbeing of children through care and education. ECE will be used particularly in this study, but will also cover Early Childhood Care and Education (ECCE) and Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC).

Assessment – In this study, assessment will be described as the investigation and documentation of children’s perceptions and capacities, seeking to understand how children think and learn, to track their progress, and further facilitate learning (Dunphy, 2008).

Setting/s – Applies to the range of actual service/s provided for young children’s care, learning, and development.

Educators – Refers to staff, teachers, pedagogues and practitioners who regularly engage with children in different early years’ settings and are responsible for their care, learning, and development.

1.8 Research Overview

The dissertation contains five chapters, each focusing on a specific aspect of the research project. The first chapter provides an overview of the research, setting the context and outlining the aims and research questions to be explored. Moreover, the rationale behind the study is described, along with a brief explanation of the research design to be used.

Seminal and contemporary literature relevant to the study is extensively discussed in the second chapter, spanning research, policy, and practice.

In chapter three, the theoretical underpinnings of the research is highlighted, followed by an explanation and justification of the research methodology and design applied. The limitations and ethical considerations concerning the study are also addressed in this section.

Key findings from the data gathered are outlined in chapter four, according to themes that have surfaced in the data analysis. These will be discussed in detail and linked to relevant literature presented beforehand in chapter two.

Finally, chapter five reviews the conclusions yielded from the study, and raises possible implications, as well as recommendations for practice and future research that arise from it.

CHAPTER 2: LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Introduction

This chapter outlines a body of literature relevant to the study, spanning theory, policy, and research. The chapter opens with a presentation of dominating perspectives on children and children’s learning that influence assessment, followed by a discussion of the links between curriculum, pedagogy, and assessment. Models of early childhood education, in particular the Montessori approach, High/Scope curriculum, and Reggio Emilia philosophy will be reviewed next, examining the extent to which assessment is emphasised in each and how they may be carried out. The focus will then move to the topic of assessment in depth in the succeeding section, expounding on the definitions, purposes, methods and strategies associated with it. A brief overview will be given of assessment as depicted by Aistear, the Irish Early Years’ Framework, and issues surrounding educators and assessment will also be discussed, bringing to light some factors affecting assessment practice in the early years.

2.2 Perspectives on Children and Children’s Learning

Frameworks and guidelines surrounding ECE are underpinned by particular views about young children, their development, and the roles they play in different units of society (Woodhead, 2006). Whether children’s learning is supported or inhibited will depend on the strong influence of the views held by educators (Carr, 2011). The following section reviews three perspectives on children and children’s learning and their implications for assessment:

2.2.1 Developmental Perspective

Dunphy (2008) describes childhood as the period where development takes place in a much greater capacity than any other period, and that its variable nature creates challenges for assessing early learning and development. A developmental perspective looks at the normative characteristics of children’s growth in different domains, and underscores the importance of ‘appropriateness’ in curriculum and pedagogy (Woodhead, 2006). This perspective also stresses childhood as a formative period, where positive relationships with others are seen as essential, and the potential for negative experiences to have a detrimental impact on children’s development are emphasised (Woodhead, 2006). The developmental characteristics of each child are seen as an important influence on their learning, and their progress in their knowledge, skills, dispositions, and feelings are considered as essential goals (Katz, 2010). Here, there is a prevailing notion that children undergo sequential, predictable stages (Walsh, 2005), the knowledge of which can be useful in planning for curriculum and assessment (Katz, 2010). Hence, many principles underpinning developmental perspectives would place importance on assessing children’s development and measuring it against expected developmental ‘norms’.

The National Association for the Education of Young Children (2009) proposes a framework for best practice that supports children’s learning and development. They put forward the concept of Developmentally Appropriate Practice (DAP), which underscores principles of child development and learning in informing practice to promote children’s well-being. Curriculum set on the principles of DAP considers the children’s interests and developmental levels, but is mostly educator-framed, in that making judgements and planning for the curriculum is mainly seen as the adult’s responsibility (Abu-Jaber, Al Shawareb, & Gheith, 2010; Obidike & Enemuo, 2013). Assessment within the context of this perspective provides a critical focus on outcomes, and heavily relies on the adult to determine which of these set benchmarks are met. Nevertheless, Cohen (2008) asserts that the discourse of DAP has progressively been regarded as what Foucault describes as a ‘regime of truth’, one that “generates an authoritative consensus about what needs to be done in that field and how it should be done (p. 9)” and discounts other perspectives or world views. Adopting labels such as appropriate and inappropriate leads to a process of normalization, shaping ECE settings as homogenous sites and classifying everything according to these dominating binaries (Cohen, 2008). Fitting practice into binaries may lead to feelings of conflict for educators when faced with instances that do not neatly fall into the categories set (Viruru, 2005). Walsh (2005) echoes the challenging of the apparent overemphasis of this perspective in the field of ECE, arguing that although it is important to give weight to children’s development, it is equally important to expand one’s horizons to include multiple perspectives.

2.2.2 Socio-cultural Perspective

In the socio-cultural perspective, children’s development is seen in the context of the culture and society that they belong in, highlighting how children gain competencies and identities significant to their culture through their engagement with people and their surroundings (Dunphy, 2012; Woodhead, 2006). While some concepts in this perspective may have developmental roots, there is also a focus on children as partners and co-constructors in the process of their development (Basford & Bath, 2014). Interaction is a vital element in these social constructivist theories, where it mediates learning through active engagement with the child, curriculum, and learning context (Dunphy, 2012; Payler, 2009). Educators’ interactions with children are key for building collaboration of knowledge in the assessment process (Dunphy, 2008). Moreover, understanding the interactions and processes that underlie children’s learning is essential to knowing how to assess it, and to shaping the assessment process so that it includes and involves children (Dunphy, 2008).

Vygotsky (1978) viewed the role of the adult as integral to children’s process of learning, not only as someone who imparts information, but one who supports and extends children’s understanding (Whitebread, 2008). Vygotsky identified two levels of development – the ‘level of actual development’ where children can operate on their own through their established skills, and the ‘level of potential development’, or what they can achieve with the support of a more experienced adult or peer. Moreover, he describes a space called the ‘zone of proximal development (ZPD),’ the distance between the two developmental levels, or those functions that are still in the process of maturation (Vygotsky, 1978; Whitebread, 2008). It is in this space, Vygotsky asserts, where learning occurs, because it pushes children towards higher developmental levels rather than staying static. This approach is one that effectively integrates teaching and assessment together; through the adult-child collaboration within the ZPD educators can determine the capabilities of children and the kind of assistance that they need, as well as gauging how the assessment impacts children’s progress (Dunphy, 2008). Siraj-Blatchford, Sylva, Muttock, Gilden, and Bell (2002) suggest that educators become effective when they develop interventions that consider a child’s ZPD. The contributions of both adults and children, their interactions, communications, and collaboration are core elements of this concept (Dunphy, 2008).

Often linked to the concept of ZPD is ‘scaffolding,’ (D. Wood, Bruner, & Ross, 1976) or the process where adults engage with children within their ZPD. Here, adults facilitate aspects of a task so that children initially keep their attention on what they can manage, before slowly leading them to take more responsibility as their proficiency increase (Dunphy, 2012; D. Wood et al., 1976). Rogoff (1998), however, contends that the ZPD and scaffolding are separate concepts, characterising the latter as a “specific technique focusing on what experts provide for novices (p. 699)” and how educators respond to children’s successes or failures. Jordan (2004) points to scaffolding as adults being more in control, and suggests that ‘coconstruction’ views the child as having a more powerful role in the interaction process. Coconstruction indicates a sense of togetherness of educators and children, and concentrates on building meanings rather than reaching specific outcomes (Jordan, 2004). In assessing children to support their learning, educators must go beyond scaffolding and acknowledge children’s own contribution to the process (Dunphy, 2008).

Within this perspective, outcomes are still considered vital to children’s learning. However, while still predominantly adult-led, assessment strategies consider children’s individual perspectives and invite them to participate in the process through collaboration and coconstruction.

2.2.3 Child’s Rights Perspective

Children’s “entitlement to quality of life, to respect, and to well being (p. 27)” is a major priority in the child’s rights perspective, as well as the adult’s role in enabling children to realise this in practice (Woodhead, 2006). The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child General Comment No. 7 (2006) supports the view of children as rights’ holders, and maintain that the early years is critical for the realization of these rights. In this perspective, concepts such as ‘children’s agency’ and participation arise to allow children to have a role in shaping their own childhoods (Woodhead, 2006). Pufall and Unsworth (2004) expound on this, stating:

By voice we refer to that cluster of intentions, hopes, grievances, and expectations that children guard as their own. This voice surfaces only when the adult has learned to ask and get out of the way. By agency we refer to the fact that children are much more self-determining actors than we actually think. They measure issues against their own interests and values, they make up their own minds, they take action as a function of their own wills – that is, if the more powerful class, the adults, allow them to do so. (pp. 8-9)

Children are viewed as social actors, who have their own voices and an active relationship with their society, participating beyond their families and homes (Dahlberg, Moss, & Pence, 2007). What is more, children have their own interests (United Nations, 2006), which may not always correspond with the expectations of adults (Dahlberg et al., 2007). Although some may construe this perspective as challenging the power and control of adults, Smith (2007) maintains that realising children’s participation rights is essential to facilitate inclusion, foster resilience, and empower children to enact change. Nevertheless, Pugh (2014) contends that while there may be movement in this ‘new social studies of childhood’ impacting the field of ECE, there is still the pervading consideration of children and childhoods as “a site upon which existing theory is only applied (p. 76)” instead of one where theories are constructed, overlooking the value of potential fields of knowledge that can be gained from this perspective.

Therefore, if children are to be regarded as capable participants in the learning process, they must be listened to and invited to participate in democratic dialogue and decision-making (Dahlberg et al., 2007), as well as given the opportunity to become self-assessors of their own learning (Fleer & Richardson, 2004). According to Dunphy (2008), regarding children as agents is considered of vital importance in developing their identity and self-esteem, taking into account their active role in the process of assessment. The involvement of children in the assessment of their own learning and encouraging a reflective attitude presents opportunities not only for the children, but for educators as well. Research evidence affirms that children’s perceptions of progress may be different from that of adults’, and suggests that this mismatch, and the absence of the child’s view in the assessment process, may lead to children adopting adults’ meaning of progress at the expense of their own (Critchley, 2002). Because children develop differently from each other, Critchley notes that establishing individual goals with them may yield benefits, and that target-setting and reviewing are important aspects of meaningful self-assessment. Similarly, Carr (2011) argues for the significance of children’s self-reflection, adding that it is possible for educators to design strategies to apply this in practice. It can be supposed, then, that assessment leaning towards the child’s rights perspective entails decisions made through negotiations between children and adults, where listening to the child’s voice is not only considered, but deemed essential.

2.3 Curriculum, Pedagogy, and Assessment

Curriculum is seen at present as something that encompasses much more than a formal structure where subjects are to be taught or information delivered (Duffy, 2010). In the context of early childhood education, curriculum covers everything that children experience in the setting – the policies and practices, interactions, environment, and also assessment – whether planned or unplanned (Duffy, 2010; French, 2007; Obidike & Enemuo, 2013). In Ireland, the National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (n.d.) endorses the joint use of Aistear and Síolta to enhance curriculum provision to support children’s learning and development. To assist educators in achieving this, the NCCA developed the ‘Aistear Síolta Practice Guide’ to promote an “emergent and inquiry-based curriculum (p. 10)” grounded on these two key documents. Here, curriculum is described as:

…more than the daily routine or a list of activities and experiences. It is more than naming a philosophy or approach to early childhood care and education. It is about the totality of children’s experiences – the broad goals for their learning and development, the activities and experiences through which they can learn and develop, the approaches and strategies practitioners use to support and enable them to achieve their goals and the environment in which all of this takes place. The curriculum also includes the unintended impact of experiences, routines and practitioners’ values and beliefs on children which is often referred to as the ‘hidden curriculum’. (p. 9)

This is distinguished from pedagogy, which involves the instructional techniques and strategies used to facilitate learning and to “provide opportunities for the acquisition of knowledge, skills, attitudes and dispositions within a particular social and material context (p. 28)” (Siraj-Blatchford et al., 2002). A study by Lee (2006) revealed that educators share particular beliefs about appropriate pedagogy in the preschool years, having a consensus that pedagogy should promote an atmosphere of fun for children. Many also expressed the need to support children’s social, emotional, and physical development, allowing them to explore and discover while taking into consideration each child’s uniqueness and choice.

Assessment features in both curriculum and pedagogy, allowing educators to construct positive experiences for children that facilitate their development and respect them as distinct individuals. Síolta (DES, n.d.) describes pedagogy as a holistic approach in interacting with children in order to support their development, as expressed through the curriculum. Gullo and Hughes (2011) argue that an appropriate curriculum for children should go beyond a “one-size-fits-all” model and make provision for children’s ‘normative’ development while at the same time allowing for variation that addresses their individual needs.

There is an inextricable link between curriculum, pedagogy and assessment in the early years. Having a nurturing pedagogy, where the term ‘nurture’ represents a more active, engaged quality with regards to adult-child interactions, promotes a shared construction of knowledge, where curriculum and assessment approaches are shaped from interactions with children and reflections on observations (Hayes, 2007). Pedagogical framing denotes informed decision-making in relation to the curriculum, which includes planning, organizing the time and environment, implementation of activities, assessment, documentation, and evaluation (E. Wood & Attfield, 2005). In what can be interpreted as an intricate cycle, the National Research Council (2001) also establishes this link, describing how assessment can inform pedagogical and curriculum decisions.

2.4 Models of Early Childhood Education

Models of early childhood education serve as points of reference for everything that happens within ECE settings. Each having developed from different contexts, the models are grounded on particular philosophies relating to children, their learning, and how best to approach it. The particular models outlined below – the Montessori Approach, High/Scope Curriculum, and Reggio Emilia – were chosen for their relevance in the Irish context, as many elements from these models are used in daily practice.

2.4.1 Montessori Approach

In the Montessori approach, children are seen to develop in distinct stages, and preparing the environment to support children at each stage is critical for them to achieve their potential (Isaacs, 2010). Maria Montessori (1870-1952) developed this approach while working with children with special needs, then after with those living in the slums of Rome (C. P. Edwards, 2003). The Montessori environment is constructed with respect for the children, confident in their capacity to make choices and establish their independence (Huxel, 2013). The educator’s role is pivotal in ensuring that this is so, and to forge meaningful connections between the environment and the child (Isaacs, 2010). The environment is also where children, particularly those from birth to six, seek “sensory input, regulation of movement, order, and freedom to choose activities and explore them deeply without interruption (C. P. Edwards, 2003, p. 36)”. This approach uses working materials which are designed to be selfcorrecting, allowing children to engage with them even without the intervention or supervision of adults (Lillard, 2013).

A key element of the Montessori approach is that it is individualised, where children take part in self-directed activities, and through systematic observation educators are able to recognise children’s needs and address them accordingly (C. P. Edwards, 2002; Huxel, 2013). Observing and documenting the needs of individual children is an important part of the educator’s role in this model of learning. The extent to which educators are able to facilitate and support the learning and development of different children is dependent on their ability to be reflective in the interpretation of children’s observed behaviour, which can also be used for record-keeping and assessment, and for planning and reworking the environment (Isaacs, 2010).

2.4.2 High/Scope Curriculum

The High/Scope Curriculum was developed through the leadership of David Weikart as a response to address the needs of at-risk children in Ypsilanti, Michigan (Hohmann, Weikart, & Epstein, 2008). This particular curriculum promotes an approach called ‘active participatory learning’, where there is a partnership between children and educators, and both are involved in the learning process (Epstein, 2007). In this curriculum, children are encouraged to self-assess through the ‘plan-do-review sequence’, where they “make choices, carry out their ideas, and reflect on what they learned” (High/Scope Educational Research Foundation, p. v), which fosters reflection, purposefulness, and independence (Epstein, 2007).

The High/Scope practice is guided by principles illustrated in the High/School Preschool “Wheel of Learning” (Fig. 1), where active participatory learning is used as a means to engage with the curriculum outlined by key developmental indicators (KDIs), or behaviours that reflect children’s unfolding abilities across domains (Hohmann et al., 2008). In turn, different elements influence the degree to which these KDIs are achieved, demonstrated by the sections indicated at the periphery of the wheel. Included in this is assessment, where educators undertake daily planning sessions and take regular anecdotal records (Hohmann et al., 2008). In addition, the High/Scope Curriculum uses the Preschool Child Observation Record (COR) for each individual child, and the Preschool Program Quality Assessment (PQA) to evaluate their curriculum.

2.4.3 Reggio Emilia

The Reggio Emilia approach flourished from the guidance of Loris Malaguzzi (1920-1994), in the region of the same name in Italy. It emerged from a post-World War II vision of reconstructing society through education (C. P. Edwards, 2003). Having reciprocal relationships is an important aspect of the Reggio philosophy, where educators and children learn together as they take part in different projects (Thornton & Brunton, 2009), and where parents are considered important partners in the organization of the school (Malaguzzi, 1993). Children are respected as competent beings, and the curriculum is not predetermined but rather flows organically from children’s first hand experiences and their explanations and theories about their surroundings (Thornton & Brunton, 2009). At the same time, children are supported to confidently express themselves through different ‘languages’, or the “many modes of symbolically representing ideas, such as drawing, painting, modelling, verbal description, numbers, physical movement, drama, puppets, etc. (Malaguzzi, 1993, p. 11)”.

Observation, interpretation, and documentation in this approach are woven together, along with the pedagogy of listening, to allow learning to be visible (Rinaldi, 2004). This documenting of the process and product of engaging with children in different projects creates a concrete record that portrays what had happened, serving as a springboard for further learning (C. Edwards, Gandini, & Forman, 1998). Apart from this, educators can also use documentation as a research tool and for professional reflection, and to engage the larger community (C. Edwards et al., 1998).

2.5 Focusing in on assessment in the Early Years

2.5.1 A broad look at assessment

Assessment in the early years looks at, examines, and documents children’s perceptions and capacities, seeking to understand how children think and learn, to track their progress, and further facilitate learning (Dunphy, 2008). It is a medium for social thinking and action, expressed through mutual feedback and dialogue (Fleer & Richardson, 2004). Gullo and Hughes (2011) describe effective assessment as continuous, comprehensive, and integrative, seeing it as “a process, and as such be ongoing, use multiple sources of information, be integrated with teaching and curriculum and provide a means to communicate with others, including families, about children (p. 327)”. E. Wood and Attfield (2005) identify six forms of assessment: formative (interpreting children’s progress and planning accordingly), ipsative (assessment that is oriented to the child instead of external norms), diagnostic (observing specific contexts and planning interventions), summative (overview of child’s progress during a certain period), evaluative (reviewing the effectiveness of curriculum and provision), and informative (using assessment information to share with parents and other stakeholders).

Having a holistic picture of the child entails using both formative and summative assessments, where the former is seen as a tool for planning while the latter gives a glimpse of a child’s capacities during a given period (Linfield, Warwick, & Parker, 2008). This allows not only for children’s achievements to be recognised, but also their learning potential (Nutbrown & Carter, 2010). At the same time, assessment holds an evaluative purpose, which helps educators see how the interventions and support they have prepared impact children (Nutbrown & Carter, 2010; E. Wood & Attfield, 2005). Black (2013) affirms the integral role of both formative and summative assessment practices in teaching and learning, asserting that they must support each other. It can be seen, then, that assessment holds a knowledge function and an auditing function, both of which are interdependent of each other (E. Wood & Attfield, 2005). The knowledge function focuses on understanding children’s needs, characteristics, and identities, as well as using assessment to delve deeper into curriculum and pedagogy (E. Wood & Attfield, 2005). Meanwhile, the auditing function is more summative in nature, presenting a child’s competencies alongside curriculum objectives or goals. What is most important in early years’ assessment, Nah (2014) notes, is that it is utilized for the benefit of the children, rather than for the purposes of ranking them.

Standardized assessments, where examiners strictly follow instructions for test administration, pose dangers in restricting the expression of diversity, and undervaluing children’s individual needs and learning styles in ECE settings (Gullo, 2006; Wortham, 2003). There are instances that might necessitate this type of assessment, but educators should not depend solely on it and must remain aware of its limitations (Gullo, 2006). To illustrate, depending on children’s ability and ease to communicate, examiners could be left with the task to infer answers from their behaviours or to gather information from parent reports (National Research Council, 2001). Also, elicited responses from children may not fully represent their capabilities, as differences may exist in language used in tests and what children use in their daily lives (Gullo, 2006). There is also the matter of validity and reliability in standardised instruments when considering the rapid development that young children undergo (Wortham, 2003). An emphasis on standardized assessment is also likely to narrow the curriculum, pushing educators to teach according to what skills are being assessed (Casbergue, 2010; Gullo, 2006). Furthermore, standardized assessments may hold biases that disadvantage children from different contexts (Gullo, 2006; National Research Council, 2001).

Bravery (2002) illustrates the implications of policies and practices contained in the social system, particularly what potential impact baseline assessment and standardised testing in the primary school have on different early years’ settings. In a survey of educators conducted in Essex, responses indicate that some current assessment practices are mainly used for recording purposes rather than supporting curriculum planning. The author points out that without formative assessment, opportunities for children’s learning and development may be overlooked. Nah (2014) has also observed that a systemic implementation of assessment through government intervention allowed for consistent practice with children and across areas of learning, as well as the involvement of families. However, there were also perceived hindrances such as less time for engagement with children, the danger of overwhelming educators with a heavy workload, and the likelihood of generating rankings based on centre or children’s achievement.

Nonetheless, there have also been issues raised with regards to formative assessment. Bennett (2011) indicates six of them (definitional, effectiveness, domain-dependency, measurement, professional development, system), encouraging a critical position to the construction and practice of assessment and a careful stance in the assertions and expectations made from it. He notes an ambiguity in the definition of formative assessment, which leads to a variability in its effectiveness. Bennett also suggests that more than pedagogical skills, formative assessment should be grounded within specific domains, and highlights the importance of interpreting evidence and the educator’s knowledge as a key to successful implementation. Finally, Bennett positions formative assessment as a piece of a bigger picture – an aspect of a larger educational context – which must be kept coherent if effective education is to take place.

In the Irish context, the notion of assessment is included in the discussion surrounding quality in ECE. In a consultative seminar aiming to gather stakeholders’ insights about the ECE sector in Ireland (Duignan & Walsh, 2004), the curriculum and adult-child interactions were found to be significant aspects considered in defining quality in the sector. Additionally, child outcomes were seen to be a means of assessing quality, which includes regular assessment, evaluation, and documentation across the different developmental domains. There was also a consensus about the need to involve children by consulting with and listening to them regarding matters that affect them, and ensure that policies and practice serve children’s best interests.

2.5.2 Aistear, the Irish Early Years Framework

he research paper on formative assessment, commissioned by the National Council for Curriculum and Assessment to underpin theory behind the Aistear framework, stresses the merit of using formative assessment in early years’ settings, stating that educators’ own assessments are a powerful influence on making decisions about children’s learning and progress (Dunphy, 2008). Aistear describes assessment as integral to educators’ interactions with children, and defines it as “the ongoing process of collecting, documenting, reflection on, and using information to develop rich portraits of children as learners in order to support and enhance their future learning (p. 72)” (NCCA, 2009). These four elements do not happen exclusive of each other, but are rather used simultaneously depending on the educator’s decision.

Aistear describes good assessment practice as one that makes sense for children and benefits them. It involves not only children, but also their families, and employs a variety of methods over time. Finally, good assessment practice is said to celebrate the “breadth and depth of children’s learning and development” (p. 73). Aistear promotes the use of documentation as a record of children’s learning and development, using a wealth of strategies to mark their achievements and plan for further learning. Documentation is also indicated as a useful tool to communicate children’s setting experiences with parents, as well as to identify the additional needs which some children have, and in this way facilitate the provision of appropriate interventions. The educator’s judgement, guided by their expertise, determines the content of the documentation, using it to invite educators to reflect and develop their practice. According to the Aistear Síolta Practice Guide (NCCA, 2015), having this documentary evidence serves three purposes:

It demonstrates children’s competence and their achievement and progress in terms of dispositions, skills, attitudes and values, and knowledge and understanding. It also makes learning visible to practitioners, children, parents and other stakeholders. In doing this, documentation provides important information to help practitioners plan for children’s further learning. (p. 2)

The framework (NCCA, 2009) outlines five methods for collecting assessment information, noting the importance of ethics in interacting with children and families. Aistear describes self-assessment as children reflecting on their own learning and development, and conversations as dialogues about adults and children’s thoughts and actions. While most conversations happen spontaneously within settings, it is also possible to initiate planned conversations with children. Observation entails collecting information by watching and listening to children as a means to enrich their learning and development, while setting tasks calls on the educator to plan activities targeting different facets of learning and development. Finally, testing is seen to affirm the information gathered about children, often using commercially available sets of criteria. These methods are distributed across the continuum between child-led and adult-led assessment, each having their own strengths and challenges, and using them in combination creates a more meaningful and genuine image of the child.

2.5.3 Partnership in Assessment

Also considered as an integral component for supporting children’s learning and development is working together with parents and families. A strong partnership with parents and families is cited as essential to quality service by Síolta (Centre for Early Childhood Development and Education [CECDE], n.d.), and is seen to facilitate effective and meaningful learning as valuable information about children is used for assessment and planning (NCCA, 2009). This collaboration supports educators in building a more holistic and accurate picture of a child, his or her capabilities and development, as the wealth of information from the home provides context and is taken into account in understanding each child (Chan & Wong, 2010; Gilkerson & Hanson, 2000; NCCA, 2009). Therefore, it is important for educators to ensure that there are opportunities available, both formally and informally, for regular communication with parents, and both Síolta and Aistear provide concrete suggestions on how to carry this out in practice (CECDE, n.d.; NCCA. 2009). Pertaining to assessment, some literature point to how educators can view this partnership as the mere gathering of information about children rather than actively inviting parents to be involved in the assessment process (Birbili & Tzioga, 2014). This is in spite of how parents were found to be capable and willing to take part in assessment processes and contribute informed insights about their children. The same research relates how ultimately, participants regarded parents as consumers of assessment, relaying information and output to them such as portfolios at the end of the year. Nevertheless, other authors describe partnership with parents as key to being better teachers, and outline possibilities of actively involving families in assessment (Gilkerson & Hanson, 2000).

2.5.4 Zooming in on documentation

It might be argued that, in spite of the issues associated with formative assessment, it does yield some benefit in the ECE context. Research evidence suggests that formative assessment has a positive impact in providing cognitive challenge and developing a partnership between children and adults to support learning (Siraj-Blatchford et al., 2002). Research also supports the value that documentation adds to formative assessment, and how it may serve as a means to address the challenges linked to traditional, standardised assessments, creating the opportunity for educators to have a richer understanding of children’s holistic development (Casbergue, 2010). Focal to assessment is the practice of observation, a process used to inform educators on supporting children’s learning and recognising their progress (Linfield et al., 2008). Observation is also a tool for reviewing characteristics of the curriculum – its “strengths, weaknesses, gaps, and inconsistencies (p. 113)” – as well as the provision provided (Nutbrown & Carter, 2010). However, observation is meaningless without reflection. The value of this process is seen when time is taken to contemplate and interpret what has been observed to plan and guide curriculum and practice (Hayes, 2007; Nutbrown & Carter, 2010). Forman and Hall (2005) also make the case for determining children’s beliefs, expectations, and assumptions through observation to spark meaningful, high-level quality conversations with them. They contend while observation is helpful for learning about children’s interests, developmental levels, skills, and personalities, it does not actually lead to having more breadth and depth in conversations that support learning. This breadth and depth can only be achieved by looking deeper than just a transcription of what children say and do, and contemplating the meaning behind these (Forman & Hall, 2005). Documentation of these observations and reflections, according to Fleer and Richardson (2004), operates in three ways. First of all, it serves to foster coconstruction of knowledge between learners and teachers. Secondly, it guides constructions of competence and competent learners. Lastly, it develops learning pathways to promote further learning.

The notion that documentation only serves to provide evidence of children’s progress is challenged by Bath (2012), who instead considers it a pathway to communication and cooperation between children and adults. The author presents documentation as deciding, decentralising, (less) disciplining, didactic, and dialogue – highlighting some issues that arise from practice. Bath describes current practice of documentation in the English context as mostly constraining, primarily carried out by and intended for the use of adults (deciding). This leads to documentation that has a more summative characteristic, and she points to the redistribution of responsibility and control to educators, children, and even families as a countermeasure to maintain a formative approach (decentralising). It also involves listening to children (didactic), and allowing them to participate in the documentation process (dialogue). Finally, documentation leads to a critical examination of discourses about children and childhoods prevailing in practice ((less) disciplining). The democratic practice of evaluation within the ECE sector indicates a collaboration and co-construction of knowledge and learning that the whole community identifies with (Moss, 2008). The lack of involvement of children in assessment and documentation processes is considered a missed opportunity to allow for children’s self-expression (Bath, 2012). Children take an active part in conversations where they have interest and knowledge about the topic, the likelihood of which increases when educators allow for them to communicate and be listened to (Carr, 2011).

A number of studies support the view of children as capable beings and reinforce the value of documentation in the ECE context. Children are found to be skilful communicators (Karlsdóttir & Garðarsdóttir, 2010), and the documentation process makes way for meaningful dialogue to occur between educators and children (Buldu, 2010). Through documentation, children’s strengths and capabilities are made known to educators, which serves as an informative tool for planning and self-reflection (Buldu, 2010; Karlsdóttir & Garðarsdóttir, 2010). As findings suggest, documentation enhances the process of supporting and scaffolding children’s learning (Buldu, 2010; Karlsdóttir & Garðarsdóttir, 2010). The movement away from a deficit model emphasises children’s self-awareness, and documentation has been shown to encourage self-evaluation and peer assessment which contributes to increasing motivation and an interest in learning (Buldu, 2010). Nevertheless, the challenge of involving children in reflecting on documentation was acknowledged, with particular reference to the time needed to adapt to the changes in the setting dynamic and assessment process (Karlsdóttir & Garðarsdóttir, 2010). It should also be noted that Buldu’s (2010) study focused on educators developing the documentation panels themselves, which were then shared with children and parents.

Both the content and process are important in pedagogical documentation, as the content offers concrete and visible illustrations of pedagogical work while the process provides an avenue for reflective practice (Dahlberg et al., 2007). In addition, documentation, when done well, is said to promote quality in early childhood programs by enhancing children’s learning, showing serious consideration for children’s ideas and work, being an avenue for planning and evaluation with children, fostering parent appreciation and participation, operating as a kind of educator research, and making children’s learning visible (Katz & Chard, 1996). Nevertheless, Dahlberg and her colleagues caution against the portrayal of documentation as an authentic representation of reality in its entirety, but rather depict it as selective, partial and contextual. For example, learning stories, which is a form of documentation used in New Zealand, focuses on providing narrative descriptions depicting children’s dispositions to learn in different situations as compared to detailing knowledge or skills (Blaiklock, 2013). Although arguments have been made pointing to learning stories as facilitative of eliciting children’s strengths and capabilities, as well as bringing to the surface children’s self-image (Karlsdóttir & Garðarsdóttir, 2010), other authors debate its effectiveness, stating the ambiguous concept and extremely variable nature of dispositions (Blaiklock, 2013; Sadler, 2002). Blaiklock (2008) also discusses the lack of objectivity in developing learning stories, as interpretations are made during the narrative writing, which leads to a subjective quality of data. Nevertheless, this is the reason Dahlberg et al. (2007) stress that through pedagogical documentation, what is deemed valuable by educators is revealed, along with their constructions of children as well as themselves as educators (Dahlberg et al., 2007). Visibility as a feature of documentation allows educators to be critical of how children and their learning are seen and represented (Bath, 2012), identifying dominant discourses in practice, and creating opportunities to challenge and reconstruct them, paving the way for new practice and a diversity of perspectives (Dahlberg et al., 2007).

2.5.5 Factors affecting assessment practice

Despite the perceived advantages of carrying out assessment in early childhood settings, there are also challenges encountered by educators in realizing this in practice. For instance, a focus on ensuring a smooth transition from ECE to primary school, as well as demanding parental expectations, bring pressure to educators working in the sector (Kitano, 2011). Research has also revealed tensions arising from the different perspectives on children and children’s learning. For instance, Korean educators are challenged with a disconnect between emphasising the traditional value of academic achievement in ECE and adopting the more constructivist approach that has been introduced from the West (Nah, 2014). This is also supported by Basford and Bath (2014), who argue that in the English context, there is a challenge in having children participate as agents in early childhood settings, not least because of frameworks with an inclination towards learning outcomes. They discuss the tensions that exist for practitioners who are influenced by competing assessment paradigms – the positivist, or developmental, and the sociocultural. The authors suggest that issues surface from this in practice, particularly the tension between assessment processes that ensure children’s participation, and those that involve a superficial record for the purposes of tracking and reporting development.

Because of the range of perspectives influencing educators, as well as the mounting academic pressure set upon the ECE sector, a myriad of assessment approaches have been observed in early years’ settings which may impact children’s learning. Differing priorities in assessment translate to a wide range of practices as educators seek to track children’s learning alongside their conceptions of development and academics (DeLuca & Hughes, 2014). For instance, Payler (2009) notes that settings that focused on learning outcomes and used scaffolding to achieve them seemed to reflect a negative perception of children as less able, which may affect their developing identities as learners. This was in contrast to settings seen to be oriented more towards care and socialisation that also promoted co-construction between adults and children. The author also presents an alternative approach observed in the preschool setting, characterised by facilitating predetermined goals in a collaborative environment. Be that as it may, it can also be gathered from research that educators are able to negotiate among the demands and expectations they are faced with, retaining some autonomy and adapting the demands and expectations to their curricular stance and assessment practice (Pyle & DeLuca, 2013). While assessment profiles differ from one educator to the next, depending on their curricular priorities and approach, Pyle and DeLuca maintain that each has their strengths, and that there is potential in integrating them.

A further challenge is with regard to the terms educators use when talking about assessment. For instance, seeking the perspectives of early years practitioners concerning baseline assessment in England, Chilvers (2002) noted the reluctance of practitioners to describe their practices as forms of baseline assessment. However, from the survey responses, it appears that most practitioners do conduct some form of baseline assessment through creating profiles and communicating with parents or previous educators.

In addition to this, there are also factors that may hinder the implementation of collaborative and participatory assessment, such as relevant professional training, a needed paradigm shift with regards to measurement and testing, and a reframing of expectations of families and the community (National Research Council, 2001). Both research studies and literature echo the need for competent and knowledgeable educators to be able to implement effective assessment in the early years (Basford & Bath, 2014; Bennett, 2011; Buldu, 2010; Chilvers, 2002; National Research Council, 2001; Payler, 2009). Knowledge is seen as important in manoeuvring through the tensions present in the field (Basford & Bath, 2014), and to decide which among the various guidance strategies and their implications will be best to use in various contexts (Payler, 2009).

Aspects such as teacher structure, adult-child ratio, and group size were found to be associated with quality of early years’ service provision, with the co-teacher structure, lower ratio, and smaller group size pointing to greater positive teacher behaviours and higher child care quality (Shim, Hestenes, & Cassidy, 2004). In the same research, the co-teacher structure is thought to be more collaborative and fosters a more constructive atmosphere for learning, creating a positive environment for educators. Apart from this, other structural aspects such as equipment, material, and financial support, especially by the leadership of early childhood settings, are considered to be essential to effectively adopting the practice of documentation (Buldu, 2010).

The demand for time and effort spent on the different aspects of children’s assessment were cited as potential roadblocks for its regular use in kindergarten classrooms, despite its perceived usefulness (Buldu, 2010; Nah, 2014). Process-oriented assessment was seen to be labour-intensive, as it involved copious amounts of observation and documentation (Chan & Wong, 2010). Time was also found to be a major determinant in allowing an organic transition from educators employing a traditional individualistic documentation approach to a more sociocultural one (Fleer & Richardson, 2004). Through teacher observations and analysis of diary entries, Fleer and Richardson found that while there was initial discomfort in the process of documenting using a sociocultural approach and an uncertainty in what to record, over time the value of such an approach was acknowledged, with the participants slowly considering the socio-cultural context in the assessment process.

CHAPTER 3: DESIGN AND METHODOLOGY

3.1 Introduction

The following chapter reviews the design and methodology adopted in the study, describing the rationale underlying the methods and instruments utilised and the process through which the research was carried out. This includes setting the context for the research sites and an outline of the sampling composition. Procedures guiding data generation and analysis will also be discussed, as well as the ethical considerations and limitations relevant to the study. A section on the author’s personal reflections is also included, to bring to light the reflexive nature of the research study.

3.2 Research Aim and Questions

The present study aims to investigate early childhood educators’ perspectives regarding assessment in the early years, with a focus on those working with children from birth to five years. In particular, the meaning, value, practice, support and challenges experienced by educators with regards to assessment are explored. It seeks to answer the following research questions:

1. What meanings do early childhood educators ascribe to assessment?

2. What value does assessment hold for early childhood educators?

3. What approaches and strategies do early childhood educators use for assessment?

4. What support and challenges do early childhood educators experience in doing assessment within their settings?

3.3 Methodological Approach

The research is qualitative in nature, and was designed as such because of its suitability to the study. Where the aims and objectives seek to explore participants’ meanings and understandings of their social world and elucidate their experiences and perspectives, the qualitative approach is fitting because it accounts for the context and natural settings surrounding the study (Creswell, 2007; Ormston, Spencer, Barnard, & Snape, 2014). By giving importance to descriptive detail, a contextual understanding of participants’ behaviour or perspective is produced (Bryman, 2012). This, precisely, is what the study hopes to achieve – to delve into educators’ experiences of assessment and draw their understandings from it. Additionally, its methodological approach is emergent, meaning data generation methods are adaptable, gathering a wealth of complex information, and the interpretation and analysis of data provides liberty in exploring a variety of ideas that are supported by participants’ views and insights (Creswell, 2007; Ormston et al., 2014). This flexibility is seen to pave the way for genuinely adopting the perspectives of those taking part in the study (Bryman, 2012). The research is framed within an Interpretivist paradigm, which focuses on how participants make sense of their experiences, and what meanings may be constructed from them (Hughes, 2010; Ormston et al., 2014). Here, the research process is inductive, developing themes and categories by making sense of the data gathered, working back and forth until the analysis is inclusive and exhaustive (Bryman, 2012; Creswell, 2007).

3.3.1 Reflexivity

In using the qualitative approach, researchers are very much embedded in the social worlds they explore (Hatch & Barclay-McLaughlin, 2006), and the present study recognises that a wholly detached stance cannot be achieved throughout the research process. As such, researchers must be reflective of the implications of their thought processes and decisions in the knowledge they construct (Bryman, 2012). To acknowledge the role of reflexivity and manage the impact of the researcher’s biases or responses, notes were taken regularly to monitor and take note of possible beliefs and behaviours that may have an influence on the study (Ormston et al., 2014). Additionally, a narrative of the author’s reflections and insights regarding the research process is included in this chapter.

3.4 Participants

3.4.1 Research Sites

The research sites chosen for the study represent the range of services available for young children in Ireland – publicly-funded, private, and community-based. Purposive sampling was used to identify eight early years’ settings as potential research sites for the study, with the help of the researcher’s supervisor. This was deemed suitable as participants needed to fit the aims and objectives set for the research, as well as for variability within the sample to be maximised (Bryman, 2012; Daniel, 2012). Purposive sampling was done to ensure that all who partake in the study have relevant knowledge of the subject matter being studied, and at the same time keeping in mind the aim of exploring the diverse perspectives of individuals (Ritchie, Lewis, Elam, Tennant, & Rahim, 2014). Gatekeepers were contacted through email or phone, before meeting them in person to disseminate the information kit.

3.4.2 Participant Composition

From each of the settings who consented to take part in the research, one educator was invited to participate in an in-depth interview about their experiences and perspectives on assessment. In total, the researcher interviewed eight early childhood educators from separate settings. This sample size was determined, in part, because of the limited time available for completing the research. Moreover, since qualitative research tends to involve rigorous, labour-intensive processes and produce a considerable amount of data, small sample sizes make certain that analysis can be inclusive and the study stays manageable (Ritchie et al., 2014). In total, the research included educators from private and community crèches, both agency and publicly-funded, as well as Early Start units. Each participant has almost a decade or more of involvement in the ECE sector, with their length of experience ranging from four to twenty-nine years. The respondents also have varied qualifications, however all have educational backgrounds related to the field. All of the educators who took part in the study work with children between the ages of birth to five, and serve different capacities in their centres, with some directly handling groups of children and others taking on a more supervisory role. The participants also adopt an assortment of curriculum models in their practice, with Aistear being the primary framework used by the majority, along with elements of High/Scope or Montessori. For a more detailed breakdown of the participant composition, please refer to Table 1.

3.5 Data Generation

3.5.1 Research Instruments

In-depth interview

Interviews, characterized by one-to-one interactions between the researcher and participant, devote much focus on the individual, allowing for a comprehensive account of their perspective and the context surrounding it (Lewis & McNaughton Nicholls, 2014). This instrument is most suited for the purposes of the study, due to its interactive nature that looks into a description and understanding of one’s social world (Miller & Glassner, 2004). In indepth interviews, there is a structure set for particular themes and topics to be discussed, but also space to dig deeper into answers given and for the participants to influence the direction of the interview (Yeo et al., 2014). The semi-structured characteristic of the interview allows researchers to bring to the surface what participants consider important in expounding their beliefs and opinions (Bryman, 2012). This probing gives way to richer information, and may lead to new knowledge or awareness (Yeo et al., 2014).

An interview schedule was developed based on the aims and objectives of the study (Appendix 3). First, the participants were asked to share some background information about themselves to establish rapport and provide context. Then, the interview proper consisted of various questions aiming to “achieve both breadth of coverage across key issues, and depth of content within each” (Yeo et al., 2014, p. 190). This included enquiring about their perspectives and practices on assessment in the early years, as well as the support and challenges they encounter in implementing this in practice. Suggestions and recommendations to enhance assessment practices were also sought by the researcher. Certain considerations were taken into account to do this. The researcher strove to use clear, open questions, and prepared prompts and additional probes that can be used when necessary. Open questions do not limit, but rather provide an opportunity for the researcher to collect a range of responses from the participant (Wilson & Sapsford, 2006).

Documentary analysis

For this study, documentary sources pertain to specific assessment tools and materials used by educators in their daily practice, including, but not limited to, checklists, kits, communication diaries, narrative reports, and portfolios. In analysing documentary sources, it is important to bear in mind that they are the product of human effort, with particular contexts surrounding them as well (Finnegan, 2006). Therefore, documents must not only be consulted, but also interpreted, probing into “how they came into being: by whom, under what circumstances and constraints, with what motives and assumptions, and how selected” (Finnegan, 2006, p. 146). A documentary analysis guide was constructed to aid the researcher in obtaining comparable data, taking account of the purpose, development, content, and implementation of the assessment document (See Appendix 4). This instrument was chosen to substantiate interview responses and explore actual materials used to assess young children in early years’ settings.

3.5.2 Research Procedure

Pilot Testing

The person invited for the pilot testing was a Montessori educator in a private crèche in Dublin, working with children from three to six years. The pilot interview lasted approximately 35 minutes, and was held in the educator’s classroom. The interview schedule was pilot tested to ensure that the instrument developed was sound, being mindful of the adequacy of language used, the order of the questions, and the prompts and additional probes that emerged throughout the process. Reflecting on this, minor revisions were made to improve the tool, specifically changing the sequence of particular items and including further clarifying questions. No information contained in the pilot test was included in the research analysis. The documentary analysis guide, consecutively, was pilot tested on selected assessment tools in use at the same crèche. As the researcher was employed as a part-time staff at the centre, she observed and made queries regarding the tools used based on the guide developed. Likewise, minor revisions were made, particularly modifying questions to draw out more meaningful and relevant information that fits with the potential data to be gathered from the interviews.

Data Generation

Data generation commenced once pilot testing and revision of tools had concluded, through contact with gatekeepers for access to participants and assessment tools used in the settings. As soon as consent had been given and an educator had been identified as willing to participate, contact with the potential participants was established. Information packs were provided for both gatekeepers and participants, which included an information sheet detailing features of the study and a consent form to be filled out (See Appendices 1 and 2). Any questions on the part of the participants were addressed by the researcher before arranging the interview. The interview was conducted in the educator’s workplace during an agreed upon date and time, using a digital device to record the session. The interviews conducted lasted from 35 minutes to an hour, and were transcribed verbatim within two weeks and stored securely for data analysis. During the interviews, the flow of the questions arose organically depending on the response of the participants. One interview was conducted with an educator who spoke English as a second language, and in this instance modifications were made to the phrasing of the questions to better facilitate the interview. Subsequently, the researcher viewed samples of specific assessment tools and materials that educators use in their practice, which were documented through notes or photos. Some centres voluntarily provided the researcher with template or blank copies of their assessment forms, and these were carefully marked with a code and stored securely.

3.6 Data Analysis