Growing up, I routinely did the very thing adults begged me not to do: I talked to a lot of strangers.

That was thanks to the World Wide Web, which was a digital wild west during my formative years in the late 1990s and into the 2000s. As a small-town nerd who couldn’t always find friends with the same passions as me, I spent many days in online communities. Long before writing professionally, I’d cut my teeth in criticism on IGN’s forums, crafting weekly reviews of Super Smash Bros. Brawl reveals. I’d become close friends with a small group of Death Cab for Cutie fans who I’d never meet in real life despite talking to them every day. My small world would only widen as social media moved outside niche forums and into large-scale apps that could connect me with even more like-minded friends.

But those digital homes aren’t built to last — a harsh truth we learned first-hand in 2023. Over the past 12 months, we’ve watched the slow, sad deterioration of Twitter. What once was a powerful tool for communication steadily sank into disarray as owner Elon Musk rebranded it into X. That wasn’t just a name change; Musk’s constant tweaks have come with a rise in misinformation, a flood of low-quality content, and a reported rise in hate speech. Every day, it feels like the nail in the coffin is right around the corner as the threat of a required paid subscription looms.

Trending Deal:

While some have cheered on Twitter’s demise, others are left with a strange form of digital grief. It’s something I’ve felt many times in my internet-savvy life, but I’ve never been able to describe it to those who’ve never experienced it. That was until a few months ago when I dropped $13 on a whim on a small indie game, Videoverse. The visual novel would become my favorite game of 2023 the instant I finished it, but it’s more than a title on a game of the year list; it’s the defining game of a pivotal moment for human communication.

Into the Videoverse

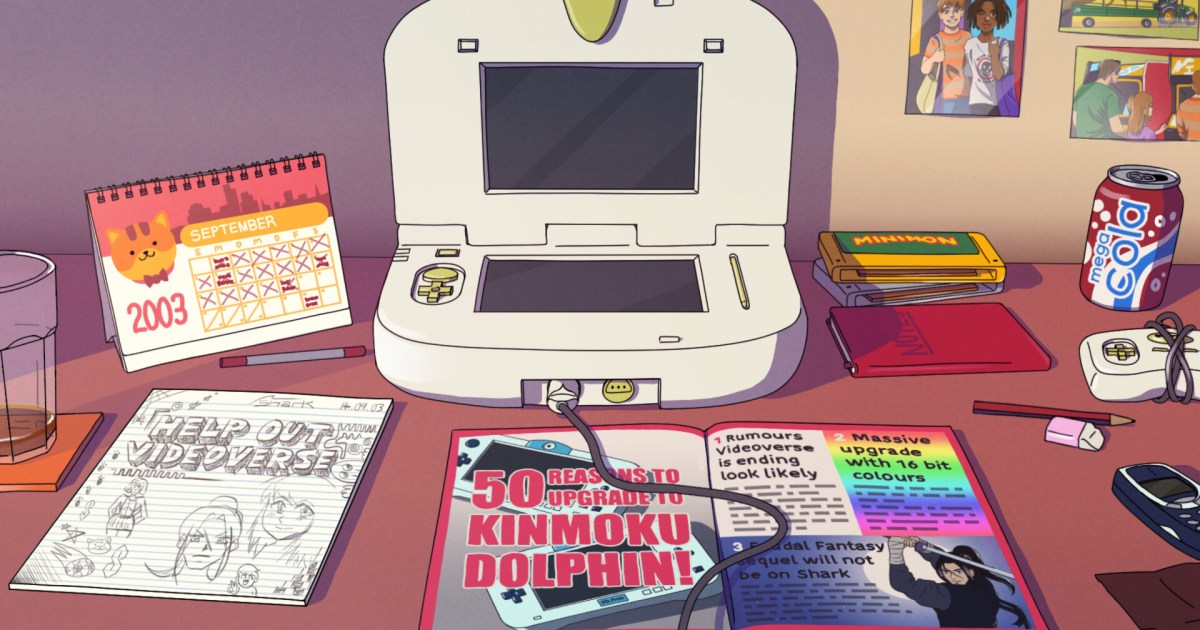

Videoverse is a visual novel set in the 1990s, where the hottest video game console on the market is the fictional Kinmoku Shark. Visually modeled a bit after the Sega Dreamcast, the platform has a free built-in social media app where players can share drawings and posts, as well as video chat with a camera that comes with the system. The choice-based narrative follows Emmet, a gamer and aspiring artist, coming of age on the platform as he connects with other fans of Kinmoku, the Nintendo-like corporation behind the system.

The project is the brainchild of Lucy Blundell, who uses Kinmoku for her own studio name. Blundell grew up in a fairly small village that only had a handful of video game fans. That had her spending a lot of time online growing up, as she hung out in gamified social spaces like Neopets and RPG Chat. She was the kid every parent fears, meeting boyfriends on digital spaces like MySpace and World of Warcraft.

Experiences on sites like DeviantArt would go on to influence Videoverse, but the initial inspiration would come from something even more niche: Miiverse. Blundell became interested in the niche social media app that came packaged with Nintendo’s Wii U, imagining what it would be like to make a dating simulator set within it. It was a backburner idea while working on another project, but Blundell tells me she was drawn in by the ill-fated app’s tragic end.

“What attracted me most was that it had such a dramatic ending,” Blundell tells Digital Trends, discussing Miiverse’s shutdown in 2017. “There was a date, and it was like, ‘That’s it, we’re switching it off!’ That’s crazy! Usually, it’s like they update it, and people move on. Twitter, there’s a buyout and things change. It’s usually a slow death of these things. But Miiverse was like, nope, it’s gone! And I just thought that was brutal. I wanted to explore what the people who were really into it were going through … I logged in on the last day, but I didn’t post anything. I was just like, look at these poor people! They’re so upset but also so thankful they had it.”

While Videoverse is a sincere and grounded story about a young kid finding connections online, it’s also a digital apocalypse story. Early in the narrative, Kinmoku announces that it plans to launch a new console, the Kinmoku Dolphin (a nod to the GameCube’s old code name). That change will bring a makeover of the company’s free Ocean Online service, which will move to a paid subscription model on Dolphin after shuttering the app entirely on the Shark. There’s an uneasy layer of tension throughout; each user is at risk of losing their entire social world.

I find it quite hard to make art that’s totally wholesome.

There’s hope in that tale, as Videoverse largely celebrates the positive power of the online community, but Blundell is careful not to sugarcoat some of the harsh realities of social media (Blundell notes that her original draft was much uglier). One optional side-story has players hunting down the app’s “secret” with the help of the anonymous Uncle From Kinmoku — a reference to the old “my uncle works at Nintendo” gag. The game’s darkest moment has players confronting the reality that predatory adults may be using the app to prey on kids. Uncle From Kinmoku is a stand-in for Blundell herself, who steps in to remind people of the double-edged sword of online spaces.

“Personally, I find it quite hard to make art that’s totally wholesome,” Blundell says. “That’s not to say I don’t value stuff like that. I love escapist video games or stories that are a nice, pleasant time, but I’m not the kind of person who can make things like that. It almost makes it more powerful that you see how nasty and awful some people can be, so how precious is it that we’ve found a few people who aren’t like that here? You can feel a real connection.”

Kinmoku and Twitter

Some of Videoverse’s more distressing undertones would take on some unexpected relevance thanks to its timing. The game launched in August, just a few weeks after Elon Musk would rebrand Twitter into X. That change would mark the start of a new era for the social media platform, which had already seen a string of controversial changes under Musk’s leadership. A new verification system would fuel a misinformation crisis, the site seemed to ease up on moderation in the name of “free speech,” and every day seemed to bring unpopular changes to its general legibility.

Blundell accidentally prophesied almost everything that would happen with the platform in Videoverse’s story. As Kinmoku begins moving resources to its new online service, it lets up on moderation. The platform becomes unstable, often breaking at random moments (on the day I’m writing this, external links stopped working on X for an hour). Kinmoku’s move to a paid tier echoes Musk’s proposed plan to make every new user pay a service fee for the platform. Most upsetting of all is when the site fills with trolls, nasty posts, and outright spam — something that’s become all too real on X this year.

“In the first half of Videoverse, if you report trolls enough times, you get a notification saying they’ve been banned. It’s a really great moment if you get it,” Blundell says. “But later on in the game, that doesn’t really matter. I’m reporting things, and nothing’s really happening. It’s how powerless you feel in that situation. I’m just trying to show that these big tech companies don’t really care about the community … I’ve noticed since the Musk takeover that you can see way worse posts showing up, the standards are shipped, and there are really bad advertisements being sent to you. You can report them, but it’s like, does anything come of that? It used to be that something happened and now it feels like it’s falling on deaf ears.”

Through our conversation, Blundell expresses frustration with what Twitter has become. She notes how she’s seen a drop in engagement and been subjected to nastier posts after having TweetDeck paywalled behind a Premium subscription, forcing her back to the proper app. Though she finds the timing of it all quite funny from a marketing standpoint, she notes that Videoverse’s future-predicting story comes from her universal observations on what always seems to happen to beloved online communities.

“I’m not an academic or a particularly smart person. I’m just observant. I’ve just seen the cycles of online spaces closing and moving on. And I think it happens more with tech companies, because it’s almost like we all don’t know what we’re doing. You can’t really trust that the companies are going to be there. If it hadn’t been Twitter closing down, it would have been something else. Even in the future, I feel like Videoverse will be relevant.”

I think Kinmoku is evil, but they’re not really doing anything different than Nintendo or PlayStation.

Blundell’s fierce dissection of social media and the responsibilities of the people who run those spaces intersects with her criticism of video game platform holders. Kinmoku acts as a lawful evil antagonist throughout the story, a cold and clinical corporation carelessly killing something that means so much to its dedicated users. It isn’t doing anything illegal, but Blundell uses that harsh reality to discuss the uncaring reality of big tech.

“I think Kinmoku is evil, but its not really doing anything different than Nintendo or PlayStation: charging subscriptions on top of your internet charge to access something,” Blundell says. “I get that something can’t be kept on forever and decisions have to be made, but it doesn’t mean we can’t be sad about it. I understand a lot of people were angry with Nintendo for closing that down and the 3DS shop. It’s really sad. You lose your community, you have to pay more, you lose access to lots of games you used to have access to. You’re losing the preservation of video games all for money and capitalism.”

A flower in the garbage

Though Videoverse is a sobering release in the context of X’s trajectory, it’s ultimately a hopeful story that celebrates online communities. Part of that attitude comes from the traumatic backstory behind it. Blundell suffered from a bad reaction to medication in 2019 that left her disabled, a condition she’s still recovering from four years later. Her grief became compounded just one year later when the COVID-19 pandemic struck, and both she and the whole world were forced to find a human connection online. Blundell would begin work on the project in 2020, connecting that moment to her formative days spent growing up online.

There’s humanistic beauty in the story she crafted. Emmett forms real friendships with other users on the site, who all bond together over their shared love of Kinmoku’s biggest game: Feudal Fantasy. The bulk of the tale revolves around his budding relationship with a girl named Violet, whose medical condition helps Emmett better understand and empathize with people in life situations he was previously unfamiliar with. His real world widens through the pixelated message board; a rose blooms in a sea of garbage.

It’s a bit of a lifeline for people like us.

As we discuss those themes, I mention the more cynical reactions I’ve seen to Musk’s Twitter takeover. While plenty have expressed grief over the space’s perceived decay, others have cheered on its demise. A common refrain I’ve seen has some declaring that social media is a “net negative” for society that’ll improve the world when it crumbles. Blundell believes that the reductive response is short-sighted.

“From a personal point of view, I have social anxiety and I’m disabled, so the internet is so much easier for me to communicate with people,” Blundell says. “If I have to go to an event in person or a party with a bunch of people, I’m just going to be quiet in the corner of the room and feel so isolated. In online spaces, I can connect in a much more comfortable way … I’ve connected with quite a lot of disabled artists and streamers in the last few years, and they rely on the internet for their businesses but also social networks to connect with other people.”

“It comes across as very narrow minded when people say ‘we don’t need these things!’ Maybe you don’t because you go to an office every day or have a family that supports you, but many people are stuck at home. It’s a bit of a lifeline for people like us.”

Though the Kinmoku Shark goes out of fashion by the end of the story, there’s life after Videoverse. Old friends rediscover each other on Ocean Online, like raptured souls finding each other in the afterlife. Others never come back, whether that’s because they can’t afford a fancy new system or because they’re at peace with their community’s end. In both cases, Blundell leaves a message of hope for Videoverse players working through their own digital grief — the kind of wisdom that can only come from someone who has seen dozens of social media empires rise and fall in their lifetime.

“Hang on to those who really do mean something to you. Do try and adopt other networks, like Bluesky or Mastodon. And if you’re not someone who really needs the internet that much, maybe take that time to log off.”

Videoverse is available now on Steam.

Editors’ Recommendations