By all accounts, the European Union’s AI Act seems like something that would make tech ethicists happy. The landmark artificial intelligence law, which enjoyed a huge legislative win this week, seeks to institute a broad regulatory framework that would tackle the harms posed by the new technology. In its current form, the law would go to some lengths to make AI more transparent, inclusive, and consumer-friendly in the countries where it’s in effect. What’s not to like, right?

Among other things, the AI Act would bar controversial uses of AI, what it deems “high-risk” systems. This includes things like emotion recognition systems at work and in schools, as well as the kind of social scoring systems that have become so prevalent in China. At the same time, the law also has safeguards around it that would force companies that generate media content with AI to disclose that use to consumers.

On Monday, regulators from the bloc’s three branches reached a provisional agreement on the law, meaning that, for lack of a better phrase, it’s a done deal.

And yet, despite some policy victories, there are major blindspots in the new law—ones that make civil society groups more than a little alarmed.

Damini Satija, Head of the Algorithmic Accountability Lab with Amnesty International, said that her organization and others had been carefully monitoring the development of the AI Act over the past few years and that, while there’s a lot to celebrate in the new law, it’s not enough.

Indeed, the European Parliament’s own press release on the landmark law admits that “narrow exceptions [exist] for the use of biometric identification systems (RBI)”—police mass surveillance tech, in other words—“in publicly accessible spaces for law enforcement purposes, subject to prior judicial authorisation and for strictly defined lists of crime.” As part of that exemption, the law allows police to use live facial recognition technology—a controversial tool that has been dubbed “Orwellian” for its ability to monitor and catalog members of the public—in cases where it’s used to prevent “a specific and present terrorist threat” or to ID or find someone who is suspected of a crime.

As you might expect, for groups like Amnesty, this seems like a pretty big blind spot. From critics’ perspective, there’s no telling how law enforcement’s use of these technologies could grow in the future. “National security exemptions—as we know from history—are often just a way for governments to implement quite expansive surveillance systems,” said Satija.

Satija also notes that the EU’s law has failed in another critical area. While the law notably bans certain types of “high-risk” AI, what it doesn’t do is ban the export of that AI to other nations. In other words, while most Europeans won’t be subject to certain, controversial surveillance products, companies in the EU will be able to sell those tools to other countries outside of the bloc. Amnesty has specifically pointed to EU companies’ sales of surveillance products to the government of China to surveil its Uyghur population, as well as to Israel to maintain hold over the Palestinians.

Over the past few weeks, Amnesty’s Advocacy Adviser on AI, Mher Hakobyan, has released several statements condemning aspects of the law. In reference to its law enforcement exceptions, Hakobyan said that the bloc had greenlit “dystopian digital surveillance in the 27 EU Member States, setting a devastating precedent globally concerning artificial intelligence (AI) regulation.” The law’s attitude toward exports, on the other hand, demonstrated “a flagrant double-standard on the part of EU lawmakers, who on one hand present the EU as a global leader in promoting ‘secure, trustworthy and ethical Artificial Intelligence’ and on the other hand refuse to stop EU companies selling rights-violating AI systems to the rest of the world,” he said.

Other groups have expressed similar criticism. Christoph Schmon, International Policy Director for the Electronic Frontier Foundation, said that while parts of the new law looked “promising,” its approach to law enforcement technologies was troubling.

“The final version of the deal is still in flux, but it’s evident that despite a lot of promising language on fundamental rights protection, the new regulations on biometric surveillance leave many questions open,” said Schmon, in an email. “We have always said that face recognition by governments represents an inherent threat to individual privacy, free expression, and social justice,” he added. “The law enforcement exceptions in the AI deal seem to make the ban of face recognition in public and the restrictions on predictive policing look like Swiss cheese. That said, much will hinge on technical details in the ongoing negotiations and how these rules are then enforced in practice.”

The AI Act’s policy details are still being fine-tuned and the EU’s complex legislative process means there are still opportunities for the fine print to shift, slightly. “There’s still quite a bit of work that needs to happen to finalize the exact text and the devil will be in the details,” Satija said. The final version of the bill likely won’t be finalized until sometime in January, she said.

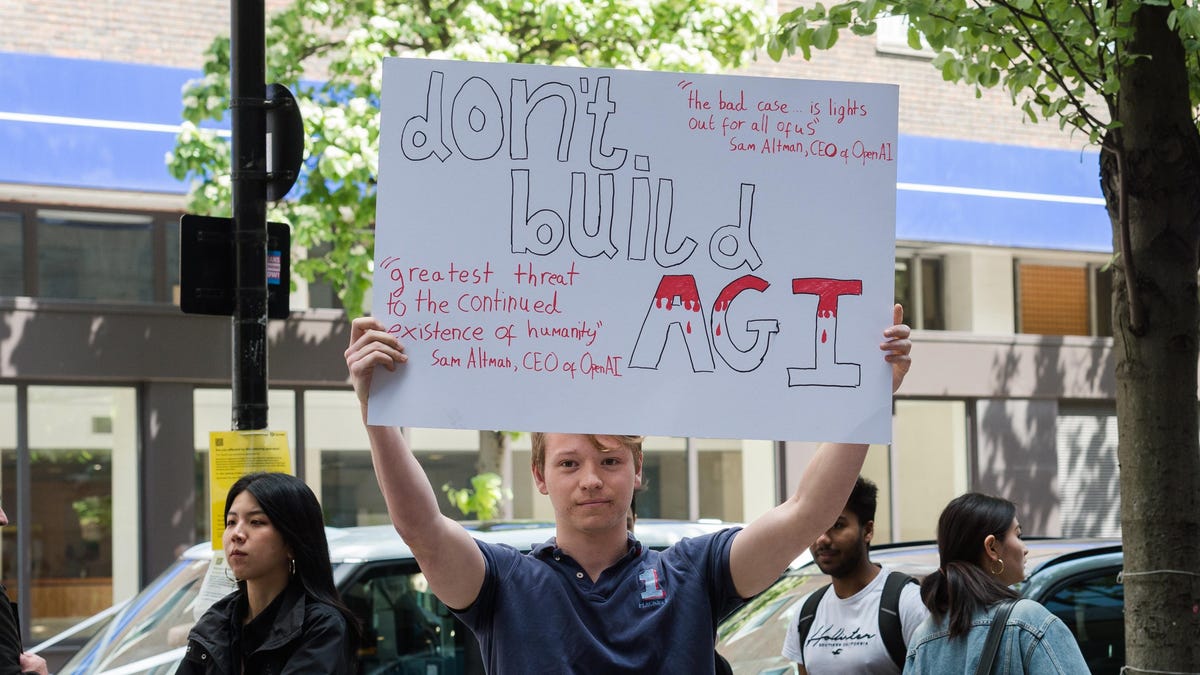

For those tracking it, the “AI safety” debate can be convoluted and, at times, quite vexing. There’s been a big tendency on the part of leaders to talk ad nauseam about the dangers that AI poses while not doing a whole helluva lot. Though the EU should be commended for spinning up a law that grapples with a lot of the challenges posed by artificial intelligence, it also seems somewhat ironic that they’ve chosen to ignore the forms of it that seem most likely to spin out of control and hurt people. After all, it doesn’t get much more dystopic than AI-fueled police surveillance. If folks are so serious about AI “safety,” why aren’t these use cases a first priority for regulators?

Question of the day: What’s the deal with “multi-modal”?

Earlier this week, folks started saying that OpenAI’s latest large language model—GPT-4.5—had leaked online. Daniel Nyugen, who posted on X about the supposed leak, described the LLM as having “multi-modal capabilities across language, audio, vision, video, and 3D, alongside complex reasoning and cross-modal understanding.” While it seems like that leak is actually a fake, one thing that is real is that the AI industry is currently obsessed with this whole “multi-modality” thing. Multi-modal systems, as far as I understand it, are ones in which an AI system is built using a variety of different data types (such as text, images, audio, and video), allowing for the system to exhibit “human-like” abilities. OpenAI’s recent integrations of ChatGPT (in which it can now “talk,” “hear,” and “see” stuff) are good examples of multimodality. It’s currently considered a stepping stone towards AGI—artificial general intelligence—which is the much-coveted goal of AI development.

More headlines this week

- Sports Illustrated CEO is out after AI “journalists” scandal. Ross Levinsohn, the now former head exec at Sports Illustrated, has been fired by the publication’s parent company, the Arena Group, after the outlet published several AI-generated stories using fake bylines. The scandal is only the most recent in a string of similar incidents whereby news outlets make the highly unethical decision to try to sneak AI-generated content onto their websites while hoping no one will notice.

- Microsoft wants to go nuclear on AI. Microsoft, the mediocre software company founded by Bill Gates, has managed to attach itself to a rising star in the AI industry (OpenAI), thus buying itself another several years of cultural relevance. Now, to power the massive AI operations that the two businesses are embarking upon, Microsoft is hoping to turn to a controversial energy source: nuclear power. It was previously reported that Microsoft was on the hunt for a person to “lead project initiatives for all aspects of nuclear energy infrastructure for global growth.” Now, the Wall Street Journal reports that the company is attempting to use AI to navigate the complex nuclear regulatory process. That process has been known to take years, so Microsoft figures that automating it might help.

- The Pope is pretty worried about an AI dictatorship. Pope Francis has been ruminating on the dangers of the modern world and, this week, he chimed in about the threat of an AI-fueled technocracy. The religious leader called for a binding global treaty that could be used to stop “technocratic systems” from posing a “threat to our survival.” Harsh words. I guess that deepfake in which he looked dope as hell really got to him.